Australia has just set a new 2035 climate target, cutting national greenhouse gas emissions by 62–70% below 2005 levels. It's simultaneously the most ambitious target in the nation's history, immediately divisive despite it objectively being “middle of the road”. Welcome to Australia's climate contradiction: targets that are politically too high, scientifically too low, and backed by a $50 billion bet that could reshape the economy, or become the world's most expensive greenwashing exercise.

The data reveals there are really three Australias at play here, and only one of them matters to investors. But first, a bit of background information.

National carbon accounting 101

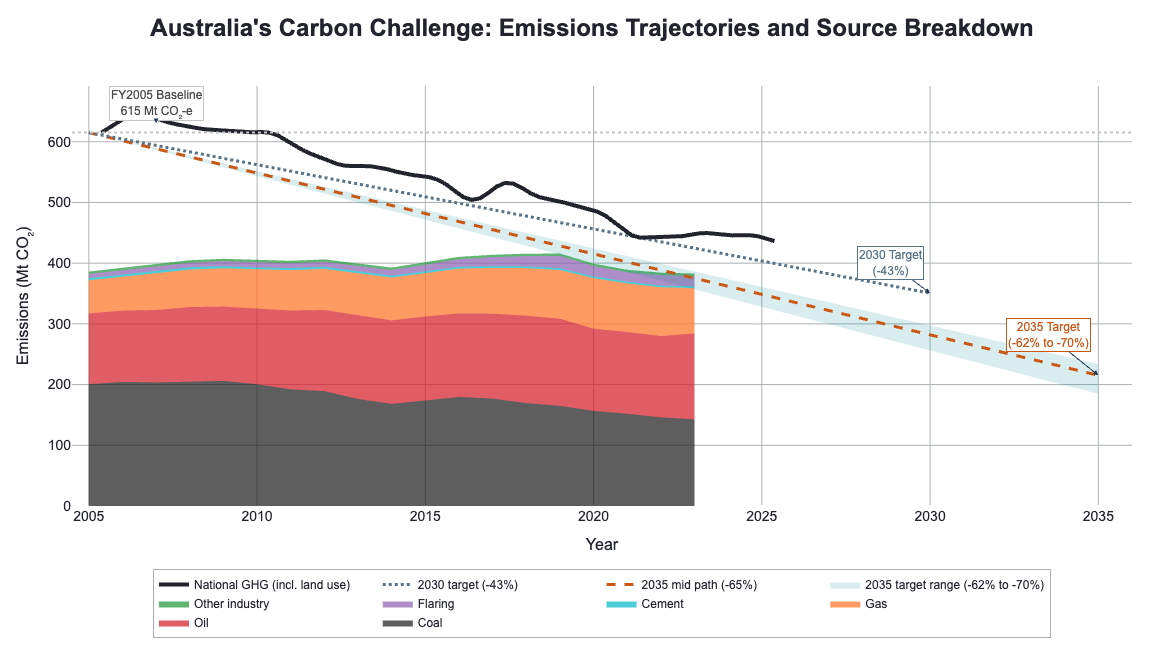

First, what does “2005 Emissions” actually mean? The black line in the chart above is the official inventory of total greenhouse gas emissions, including land-use. That line has fallen steeply since 2005, from 615 Million Tonnes (Mt) CO₂ equivalent annually, thanks largely to slower land clearing, forest regrowth, and accounting rules that credit Australia with a big natural carbon sink. It’s why Tasmania can claim “carbon neutrality” on the back of its forests. 29% reductions to date suggest major progress, but most of the existing progress has come from land-use accounting and forest regrowth rather than deep cuts in fossil fuels.

The stacked fossil lines tell a different story. Remove land-use and you see only fossil emissions, a line that has barely budged in 20 years, stuck around ~400 Mt. Coal is down nearly 60 Mt (−29%) as aging power plants close, but this gain has been cancelled out by rising oil (+25 Mt, +22%) and gas (+20 Mt, +37%). Smaller sources like cement and flaring have barely shifted.

The gap between the two sets of carbon accounting is almost entirely explained by land-use accounting, known as Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF). In 2005, large-scale land clearing, especially in Queensland and NSW, released vast amounts of stored carbon. This made the land sector a major net emitter before regrowth and stricter vegetation laws flipped it into a sink.

Since then, forest regrowth has turned LULUCF into a major carbon sink. Under UN rules, that sink is subtracted from Australia’s totals. That is why the official “all-in” inventory looks nearly 30% lower since 2005, even though fossil CO₂ from oil and gas has increased.

LULUCF is unlikely to fall much below ~–100 Mt under current conditions, and it won’t stay that low permanently. It represents a one-off accounting dividend from reduced clearing and regrowth, not a perpetual sink. The heavy lifting so far has come from trees, not smokestacks. Land sinks can flip in a bad fire year, and fossil emissions still need to fall by half in the next decade if Australia is to hit its targets.

The most tangible reductions to date have come from the electricity sector due to rapid decarbonisation and renewable installations, seeing emissions down 46 Mt (23%) since 2005, while renewable market share surged from 8% to 36%, and the economy continued to grow. Trees bought time. Turbines proved that change is possible. But overall fossil emissions are still stuck, and the hard cuts ahead will have to come from oil and gas.

Figure Source: The Conversation

The three Australias

Australia’s climate challenge can be viewed through three different lenses: how progress looks on paper, how companies are responding, and how the government is investing. Together, these three ‘Australias’ reveal the gap between perception, policy, and practice.

Australia #1: Trees vs turbines: The accounting mirage

The official numbers look impressive: emissions are down 29% since 2005. But strip away the land-use credits and raw fossil fuel emissions have hardly shifted. Coal has declined, but oil and gas have risen almost as much. The “progress” is mostly trees growing back, and the construction of new renewable power, not fossil fuels disappearing. And as that one-off land-use dividend runs out, the government is already eyeing “blue carbon” - mangroves, seagrass, and saltmarsh as the next accounting trick to keep official numbers falling.

That said, there has been one spectacular success: electricity. Emissions in the power sector are down 46 Mt while renewables have surged from 8% to 36%, all while the economy expanded. In that light, the fact that overall fossil emissions have held steady for two decades is not trivial. It shows the grid can decarbonise while demand and GDP grow.

But stability is not enough. To meet the 2035 target, fossil emissions must fall by more than 20 Mt every year, the equivalent of shutting down a major coal plant like Loy Yang annually, except now it’s oil refineries and gas fields in the firing line, a political minefield.

Australia #2: The corporate reality check

Corporate Australia is not yet aligned with these national ambitions. Fewer than 30 ASX companies have validated science-based targets set as published by SBTi, and most published targets stop at 2030. There are up to 100 companies that have registered ‘Commitments’, however haven't published explicit emissions targets. Beyond SBTi, many companies have set their own climate targets, but these vary widely in ambition and methodology, creating uncertainty about whether they align with the sectoral reductions the national target requires. The crucial 2030–2035 period, when the steepest cuts must happen, remains a blind spot. National targets assume every sector, from power to industry to transport, will deliver deep reductions. Yet the private sector roadmap for this transition barely exists.

Australia #3: The $50 billion experiment

The Albanese government has tied its credibility to the proposal of unprecedented green spending: $20 billion for transmission upgrades through Rewiring the Nation, plus the government’s $22.7 billion Future Made in Australia - including $6.7 billion in hydrogen production incentives, $7 billion in tax credits for critical minerals processing, and around $5 billion in clean-energy finance.

Treasury modelling says this could add $2.2 trillion to GDP by 2050. But it could also crash if infrastructure delays, skills shortages, and weak corporate follow-through turn the plan into a stranded white elephant. And because the target lacks bipartisan support, it’s foundations are fragile. A change of government could see incentives wound back, timelines stretched, or the entire plan reframed. For investors, that makes this not just an energy transition but a political risk trade-off.

The post-coal reality

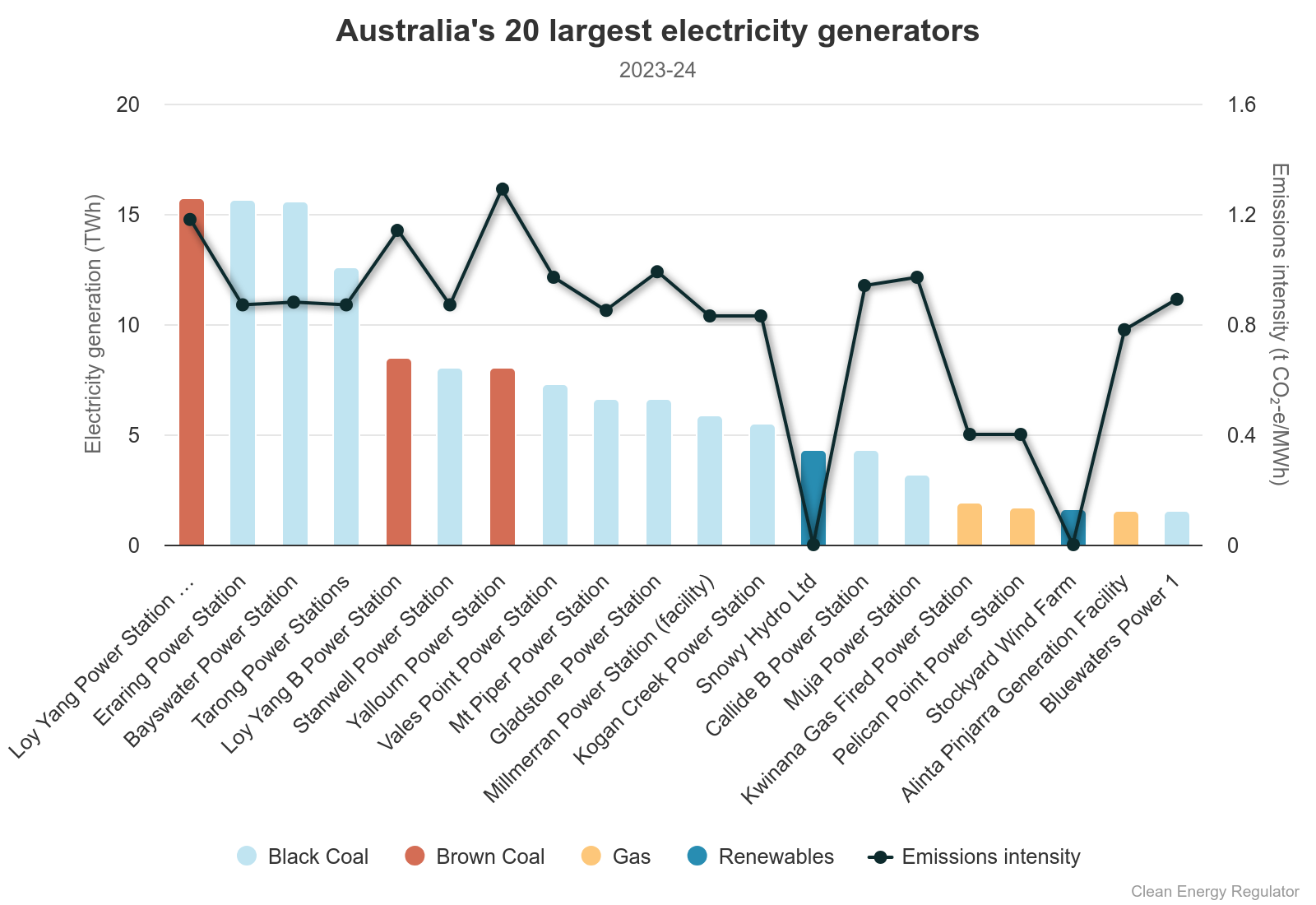

But here's the harder truth: coal closures solve the electricity mix problem, not Australia's broader climate problem. The chart below shows Australia's 20 largest electricity generators - dominated by aging coal plants like Loy Yang and Eraring that are already scheduled for closure.

By 2030, shutting these coal giants gets you most of the way to ~220 Mt, leaving a 40 Mt gap from oil, gas, industry, and transport. By 2035, after coal exits entirely, there's still a ~127 Mt gap to bridge - almost entirely oil and gas.

The remaining cuts come from industry facing 5% annual reductions under the Safeguard Mechanism, plus agricultural efficiency gains. Targets that looked politically impossible become mathematically inevitable when you map the sector-by-sector reductions.

Australia's electricity transition has clear closure dates and replacement capacity planned. The oil and gas transition has neither. This is where Australia's climate contradiction becomes an investment reality: the easy emissions are coal, the hard emissions are everything else.

Why these targets are both too high AND too low

Politically, the targets are too high. The Coalition brands them “economy-wrecking,” regional communities fear job losses, and the sheer scale of cuts required, 20 Mt per year, is daunting. Oil and gas are now on the hook, and the politics will only get harder as land sinks run out of room.

Scientifically, the targets are too low. Climate scientists argue that a 75% reduction is achievable and necessary. The Climate Council calls 62% “dangerously inadequate.” Multiple independent analyses suggest higher targets could be delivered cost-effectively, yet politics capped ambition at a level that still risks climate system breakdown.

This political-scientific gap creates massive transition risk, even though the target is objectively “middle of the road”. Companies betting on gradual change could face sudden policy acceleration. Those preparing for rapid transformation might find themselves ahead of a slower-moving regulatory curve. This creates a potential for a two-speed economy, with different sectors growing at different rates.

The two-speed economy taking shape

The proposed ~$50 billion transition spend clearly shows who wins and who loses:

Winners

- Renewables and storage, backed by massive transmission projects

- Critical minerals, with tax offsets for local processing

- Hydrogen, supported with $2/kg production incentives

- “Electric everything” from vehicles to industrial heat

Losers

- Thermal coal, with every plant due to close by 2037–38

- Oil and gas, facing Safeguard Mechanism’s 5% annual cuts with no land-use credits

- Energy-intensive industries, unless they can lock in cheap renewable power

Grey zone

- Agriculture: retains forest credits and efficiency goals

- Transport: faces EV mandates, but infrastructure rollout remains uncertain

Treasury modelling suggests the economy could be 28% larger by 2035 under an orderly transition. But three risks loom:

- Workforce: shortage of 85,000 skilled workers in renewables

- Costs: major grid projects already facing 25–55% blowouts

- Corporate lag: private sector ambition trails national targets

What this means for investors

At Emmi, our transition risk models assume climate scenarios like these net zero policies will eventually bite. Whether governments like it or not, investors, banks, and insurers are already pricing in transition risk.

The real question isn’t whether Australia hits its targets on paper. It’s whether investors, companies, assets, and sectors that drive the most material emissions are prepared for the fossil cuts implied.

Right now, the evidence shows:

- Land use has done the heavy lifting

- Renewable uptake and decarbonisation have been significant

- Fossil emissions remain flat in a growing economy

- Corporate ambition is relatively weak

This $50 billion in public spending will create winners and losers faster than markets can price.

Smart money isn’t betting on whether the targets succeed. It’s positioning for the transformation they will trigger regardless.

Because Australia can’t build a net-zero future on forests alone. The next decade will decide two things: whether coal, oil, and gas can finally be cut at scale - and whether $50 billion is enough to build a green economy in time.

Sources

- https://www.pm.gov.au/media/setting-australias-2035-climate-change-target

- https://www.dcceew.gov.au/about/news/setting-2035-target-path-net-zero

- https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/emissions-reduction/net-zero

- https://ourworldindata.org/co2/country/australia

- https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-09/p2025-700922.pdf

- https://www.climatechangeauthority.gov.au/2035-emissions-reduction-targets-advice

- https://grattan.edu.au/news/a-watershed-on-the-hard-road-to-net-zero/

- https://www.bca.com.au/business_council_report_maps_investment_enablers_and_policy_levers_to_maximise_australia_s_potential_in_the_net_zero_transition

- https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/setting-a-2035-emissions-target-is-hard-but-achieving-it-will-be-much-harder/

- https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/nggi-quarterly-update-december-2024.pdf

- https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/new-analysis-australia-can-power-past-70-and-should-aim-to-reach-net-zero-sooner/

- https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2025/06/australias-latest-emissions-data-reveal-we-still-have-a-giant-fossil-fuel-problem

- https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/publications/national-greenhouse-gas-inventory-quarterly-update-march-2025

- https://sciencebasedtargets.org/target-dashboard

- https://cer.gov.au/markets/reports-and-data/nger-reporting-data-and-registers/2023-24-published-data-highlights

- https://www.energy.gov.au/energy-data/australian-energy-statistics/electricity-generation

- https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australias-emissions-projections-2024.pdf

- https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/climate-target-malpractice-cooking-the-books-and-cooking-the-planet/